How the brain learns to read is a complex topic. This article explains for concerned parents of struggling readers how the brain learns to read using clear language and simple analogies.

Table of Contents

- Is Reading Natural?

- The Reading Brain

- The Brain’s Letterbox

- The Sound System (The First Part of Speech Comprehension)

- The Meaning System (The Second Part of Speech Comprehension)

- The Reading Highway

- Fluent Reading

- Takeaways

- Conclusion

- References

Let me start by saying that this article is called “101” for a reason!

There is a lot to unpack surrounding how the brain learns to read and scientists are continuing to discover more and more! We used my best discernment to bring you only the essentials and the things we thought you would really care about. (Because we totally understand that not everyone cares as much about the role that the medial prefrontal cortex plays in language learning as much as we do!) And our goal is to make this bite-size and as free of overly-scientific words as possible.

If you are interested in brain science and want a deeper dive, I would encourage you to read the book “Language at the Speed of Sight” by Mark Seidenberg or consider purchasing my course (coming soon!) “A Parent’s Advantage in Teaching A Child with Reading Difficulties” where we break down the reading brain in greater depth, along with some helpful visual frameworks.

While there are a countless number of interactions happening in the brain while we read, there are a few major places in the brain that contribute to the process of learning to read that we will discuss. So hold onto your thinking caps and let’s get started!

Is Reading Natural?

First things first: contrary to common belief our brains do not come primed and ready for reading.

In order for reading to be possible the brain must first have two things in place, both which begin developing at birth- vision and speech comprehension (Dehaene, 2010, p. 197). (And fortunately humans have been creative enough to invent other ways for people who do not have vision or hearing capacities to understand written language too! Those are truly amazing feats, but we won’t cover them in this article!) So the two prerequisites to reading are, “Can you see?” and “Can you understand what others are saying?” If both are a yes, the brain has the capacity for reading.

But it does not yet have the pathways for reading. I like to explain reading like soccer (or any other sport). There are some prerequisites to playing soccer that develop naturally in most babies: tracking objects and moving limbs. A healthy baby will learn to track objects without being taught. They will learn to move their limbs through observation, trial and error and then develop limb control to run, kick and jump. After these two prerequisites (object tracking and limb control) are firmly in place, the rules of soccer must be taught, and the techniques that make a good soccer player must be practiced. Then this little human be considered a soccer player.

So what’s the parallel to reading? Let’s take it back to vision and speech comprehension. A healthy baby’s vision will develop without teaching. A healthy baby’s speech comprehension will develop through listening to others talk and engaging in “conversations” with caregivers. Next, a young child’s vision begins to differentiate letters from other objects they see. Their speech comprehension advances so that they can identify individual speech sounds, and engage with conversations or books read to them. Later, the rules of reading must be taught, and the techniques that make a good reader must be practiced. Only then can this little human be considered a reader.

So reading is not natural. Even in the sharpest of early readers, the rules of reading must be taught and the techniques of good reading practiced- albeit it may happen so quickly for some, you barely notice it. For brains that have a harder time with reading, these two things (teaching and practice) are especially important. Teachers working with these kids will need to take their time and do both well.

The Reading Brain

Now let’s imagine an actual brain. There are lots of “parts” of the brain that have individual jobs. They can work on their own or in coordination with other parts to accomplish a task (like reading). I put “parts” in quotations because even though they have separate jobs (like your heart and your lungs) the brain is actually one big mass. And there are countless little pathways that connect one part of a brain to another creating that one cohesive mass of a brain. But these little connectors (called neural pathways) are continually disconnecting, reconnecting and connecting to new areas based on what it needs to know to thrive in its given environment.

So let me ask you this. Are you born needing to know how to read? Nope. And so we are not born with the areas of the brain required for reading already connected. The process of teaching and practicing the reading rules is what builds and strengthens those connections from one part of the reading brain to another.

The term “the reading brain” refers to all the areas and connectors in the brain involved in the reading process.

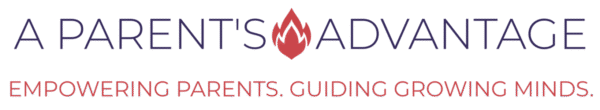

The Brain’s Letterbox

One essential area in the reading brain that develops before the process of learning to read really begins is referred to as the brain’s “letterbox” (Dehaene, 2010, pp. 55-76). It’s the brain’s special storage for letters and only letters. It is housed within the occipital lobe (the visual part of our brain) which separates everything we see into categories. Numbers get stored in one place and facial expressions in another, to name a few. In most children the letterbox develops with very little explicit teaching. By looking at books and being read to it figures out, “These squiggles on the page have their own special meaning, different from anything else we see! We should give them their own special spot!”

Then when letter instruction begins, the letterbox becomes even more specialized. It begins to draw its attention to individual shapes of letters by, for example, isolating the three distinct letters in “cat” rather than processing it as one letter shape. It also begins to store the shapes of each of these distinct letters into long term memory. But then something truly amazing happens: the letterbox realizes that for whatever reason “A” and “a” mean the same thing and so do “P” and “P” even though they look slightly different (Seidenberg, 2017, pp. 107-109). For some students this process of development and specialization takes longer than others. The jury (science) is still out on exactly why that is.

This covers the vision prerequisite to reading.

The following table will help us keep track of the most important information from each section. We will add rows as we go!

| Brain Function | Brain Location | Development Needed for Reading |

|---|---|---|

| Letters (visual) | A part of the occipital lobe called the Letterbox | Specialization to recognize the shapes and names of letters |

The Sound System (The First Part of Speech Comprehension)

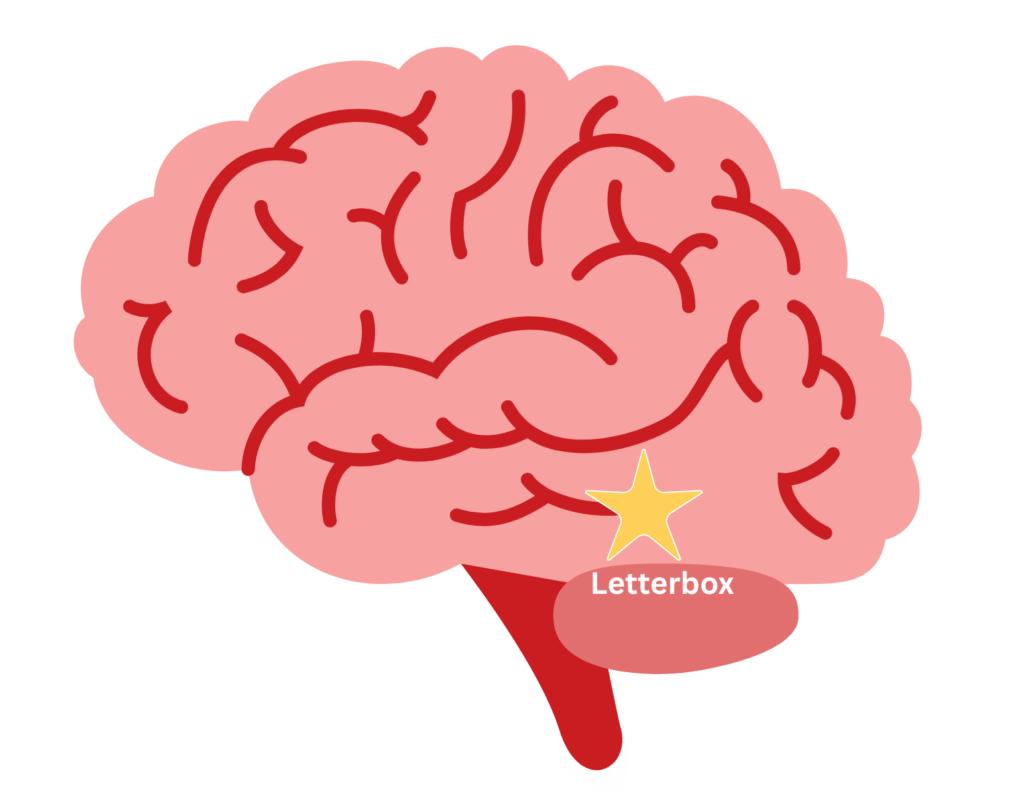

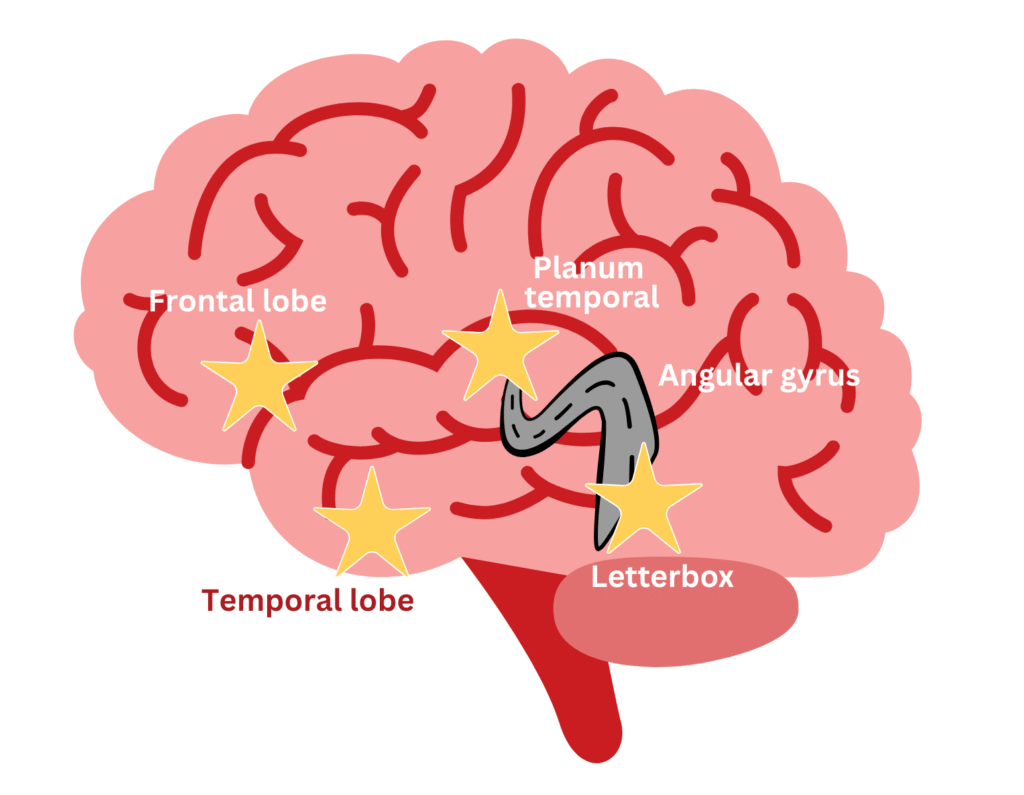

Remember that everything we have talked about so far is only visual. The brain has not yet connected any of these letters to their sounds. Sound is processed in a different part of the brain called the planum temporale (Moats & Tolman, 2019, p. 27-28). Unfortunately, this one doesn’t have an official catchy name like “letterbox”. The planum temporale is where we store all of the individual sounds spoken in our native language and helps us process individual sounds within a word.

Just like how the occipital lobe learns to categorize letters from other things it sees, the planum temporale learns to categorize spoken sounds apart from other environmental sounds like water dripping or a car horn. It figures out that, “Hmm the sounds made when a person’s mouth moves have special meaning. We should probably categorize that.” This happens very early on in the first year or so of life.

Then the planum temporale also becomes increasingly specialized by being able to pick out individual words in a sentence and eventually individual sounds in a word such as identifying that the spoken word “cat” contains the sounds /k/ /a/ and /t/.

There is a separate area of the brain in the frontal lobe that helps us to pronounce and articulate spoken words (Moats & Tolman, 2019, p. 27-28). It helps us to coordinate the muscles in our mouths required to make specific sounds in order to pronounce words correctly. The connection between this area of the frontal lobe and the planum temporale develops as a child learns to speak.

| Brain Function | Brain Location | Development Needed for Reading |

|---|---|---|

| Letters (visual) | A part of the occipital lobe called the Letterbox | Specialization to recognize the shapes and names of letters |

| Speech sounds (speech comprehension) | Planum temporale – stores individual speech sounds Frontal lobe – coordinates muscles to help us form words | Planum temporale – specialization to recognize individual sounds in a word Frontal lobe – coordination to pronounce words clearly enough to support understanding |

The Meaning System (The Second Part of Speech Comprehension)

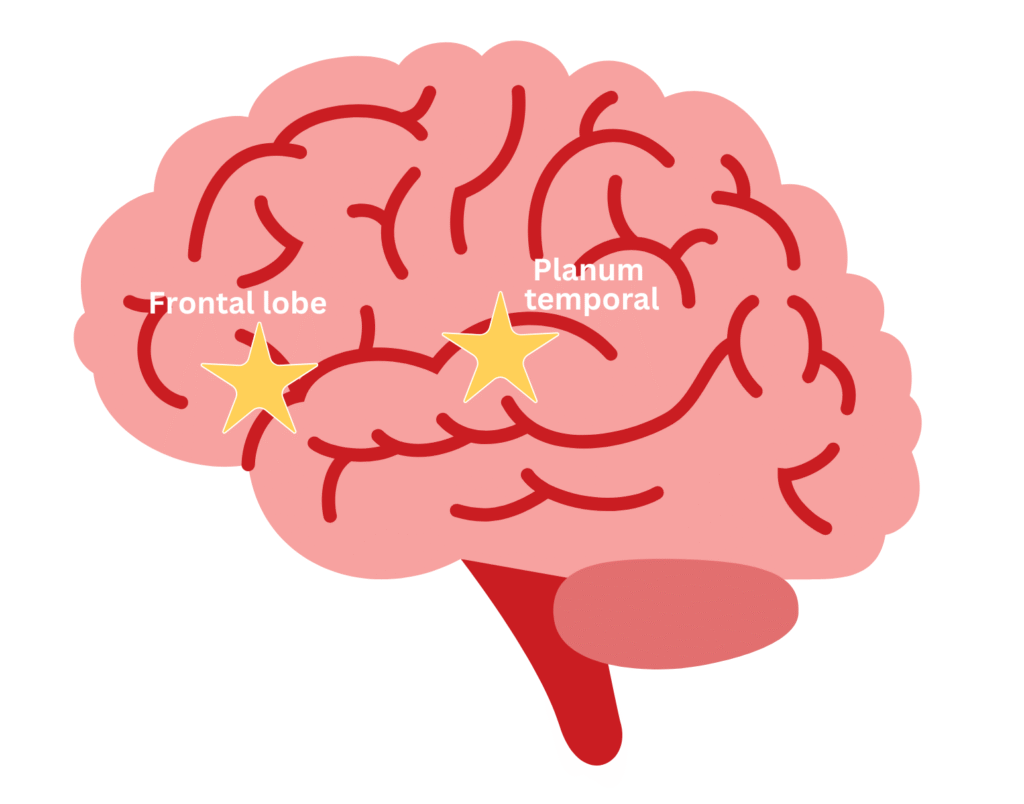

Finally, the temporal lobe houses definitions and context for every word we know (Moats & Tolman, 2019, p. 27-28). Again, this connection develops early on as a child learns to understand languages. It is often referred to as our “mental lexicon” or our mental dictionary that houses everything we know about a word; its meaning, or multiple meanings, part of speech, where it typically goes in a sentence, etc.

So these three areas, the planum temporale (individual sound storage and processing), the frontal lobe (pronunciation of sounds and words) and the temporal lobe (meanings of words) work together to create a language system that covers the “speech comprehension” prerequisite for reading. To break it down a little further, speech comprehension requires both sound knowledge and word meaning knowledge.

| Brain Function | Brain Location | Development Needed for Reading |

|---|---|---|

| Letters (visual) | A part of the occipital lobe called the Letterbox | Specialization to recognize the shapes and names of letters |

| Speech sounds (speech comprehension) | Planum temporale – stores individual speech sounds Frontal lobe – coordinates muscles to help us form words | Planum temporale – specialization to recognize individual sounds in a word Frontal lobe – coordination to pronounce words clearly enough to support understanding |

| Word meanings (speech comprehension) | Temporal lobe – houses word knowledge | Knowledge of enough words to support the understanding of a text |

The Reading Highway

So the question remains: How does the brain connect vision (letter knowledge) to speech comprehension (sound and word meaning knowledge)?

This is the magic behind how reading develops. These three systems (vision, sound and meaning) must connect.

A literacy specialist friend of mine likes to conceptualize this as building a highway. The scientific term for this “reading highway” is the angular gyrus. The angular gyrus is a bridge connecting the letterbox to the planum temporale (where we store and process speech sounds).

We have to first teach the brain that letters and sounds are related. There is no natural reason that written squiggles should represent sounds. We as humans have just agreed they do. This is the alphabetic principle- the realization that specific letters represent specific sounds. The brain says, “Hey, if we want to read, we need to bridge these two areas!” The engineer of the highway begins at the letterbox and now knows the planum temporale (sounds) is its end destination. It starts to lay the pavement. And the better the pavement’s foundation (or a child’s understanding of the alphabetic principle), the less likely they are to experience reading difficulties when words get more complicated.

| Brain Function | Brain Location | Development Needed for Reading |

|---|---|---|

| Letters (visual) | A part of the occipital lobe called the Letterbox | Specialization to recognize the shapes and names of letters |

| Speech sounds (speech comprehension) | Planum temporal – stores individual speech sounds Frontal lobe – coordinates muscles to help us form words | Planum temporal – specialization to recognize individual sounds in a word Frontal lobe – coordination to pronounce words clearly enough to support understanding |

| Word meanings (speech comprehension) | Temporal lobe – houses word knowledge | Knowledge of enough words to support the understanding of a text |

| Letter-sound connection | Angular Gyrus – bridge between the letterbox and planum temporale | Establishment of the alphabetic principle, understanding that letters represent specific sounds |

As reading instruction begins and a teacher (or a parent!) explicitly teaches children what letters make the sounds that they already know, the reading highway starts to get paved. The process of teaching these letter-sound connections is called phonics. As more spelling patterns are connected to sounds it is like adding more lanes on the highway. And the more lanes there are, the more efficiently and safely everyone can drive.

But as we have seen with the other areas of brain development, some children struggle with building this reading highway and it takes longer. Some students require more clear instruction, repetition and practice. And while that may be frustrating for you as a parent, it is ok! And it’s actually meant to be an encouragement – we are firm believers that every brain, no matter how it is made, can learn to read. If you take anything away from this article it should be this- we actually change the brain by teaching it.

Fluent Reading

After the reading highway is firmly paved, the brain can process the word as a whole, taking in all the letters at once. The letterbox can connect directly to the area of the brain that houses word meanings, skipping over the sound system. This happens only after the brain has fully mastered the phonics processes. It appears as if the reader is just looking at the word and saying it. However, anytime a reader comes across an unknown word, they must rely on the old reading highway (looking at letters and connecting them to sounds) in order to figure it out. This is why teaching phonics early on is essential.

Takeaways

So there you have it! A (hopefully) simple and clear picture of what is happening in your child’s brain as they learn to read. Here are some major takeaways to review:

- There are three processes involved in reading: letter knowledge, sound knowledge and word meaning knowledge.

- Vision and speech comprehension systems are not naturally connected in the brain.

- Phonics is the process of teaching children to connect letters and spelling patterns to their sounds.

- For some children developing the areas of the brain involved in reading may require more time and effort than for others.

Conclusion

It’s important for you to be armed with this knowledge so that you can begin to discern what practices in reading instruction are best for building this reading highway. This is your Parent Advantage! Use this knowledge to identify practices that are good for teaching reading and say something (politely!) to your child’s teacher if you notice activities that are not. (Hint: not all reading activities take the reading brain’s makeup into consideration! They are just fun reading activities that do very little to build the reading highway. (More about the best way to teach reading in this article.)

If you would like more help in how to do this you can consider booking an affordable consultation with me so I can speak to your child’s specific learning environment. You can also check out my course “A Parent’s Advantage in Teaching a Child With Reading Difficulties”. In this course we do a deeper dive into the Reading Brain, and I walk you through a method of how to identify reading instruction that does build and strengthen the reading highway. I also give helpful language to use and even questions to ask your child’s teacher if you think they are giving instruction that isn’t.

What new information did you learn in this article? Are there any reading brain related questions you still have or have now after reading? What else would you like to know about the reading brain? I’m here to help you become your child’s reading advocate, so comment below!

References

Dehaene, S. (2010). Reading in the brain: The new science of how we read. Penguin Books.

Moats, L. C., & Tolman, C. A. (2019). The Challenge of Learning to Read. In LETRS: Language essentials for teachers of reading and spelling. (3rd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 25–34). Voyager Sopris Learning.

Seidenberg, M. S. (2017). Language at the speed of sight: How we read, why so many can’t, and what can be done about it. Basic Books.